Resonance patterns

Electron Delocalization

Resonance is a concept in chemistry used to describe molecules that cannot be represented by a single Lewis structure. Instead, they are depicted as a hybrid of two or more contributing structures, which differ only in the placement of electrons, not atoms. This phenomenon occurs when electrons, particularly π-electrons or lone pairs, are delocalized over adjacent atoms, creating stability through charge distribution. Electron delocalization reduces potential energy by spreading electron density across multiple bonds or atoms, resulting in equalized bond lengths and enhanced molecular stability.

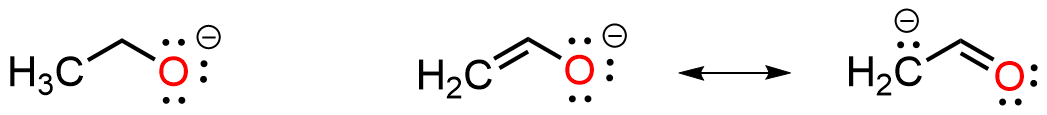

In certain types of organic molecule electrons are able to spread out over multiple atoms in order to stabilize the overall system. This requires conjugation in which orbitals are aligned in patterns that allow for extended interaction, for example between non-bonding electrons and pi bonds or pi bonds and empty p orbital(s). The examples below show a localized lone pair (left), where the non-bonding electrons are located only on the O atom, and a delocalized system (right) where the lone pair is shared between O and C. The presence of the pi system is essential for resonance delocalization and spreading the electron density stabilizes the charge and the molecule.

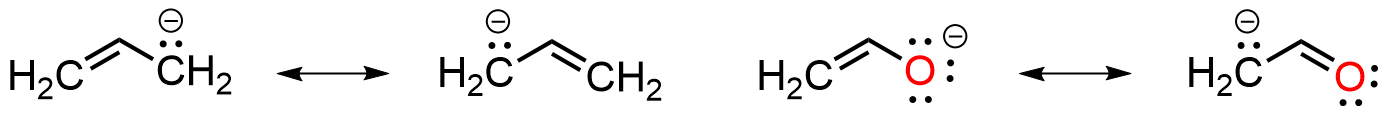

There are really only three patterns involved with delocalizing a pair of electrons; here we will call them Pattern A, Pattern B, and Pattern C. To recognize resonance in a charged molecule it must contain an electron source and an electron sink; the former is either a non-bonded lone pair or a pi bond, the latter is usually an atom capable of accepting a lone pair, for example a second-row element or an empty p orbital. Typical examples are shown below for allyl-type anions with the electron source being a lone pair and the sink being the terminal atom of the pi bond. The double-headed arrows may be used to describe the spreading of electron density in each case. This will be referred to as Pattern A.

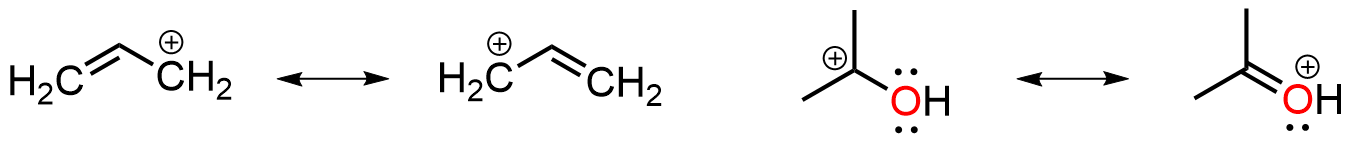

For allyl cation systems we are looking at an electron deficiency and not an electron excess as with the above anionic molecules. Here (on the left) the sink atom, usually carbon, has lost a pair of electrons from its octet, however conjugation to a pi bond allows for stabilization through delocalization. Again, we are looking at a 3-atom allyl-type system but the direction of electron spreading is reversed compared to the anions. This is Pattern B. In the example on the right, the carbocation is directly attached to a heteroatom that has non-bonding electrons (a lone pair) available to share. In such cases only two atoms are involved in resonance, however the principle of the electron donor and electron sink still applies. This is referred to as Pattern C.

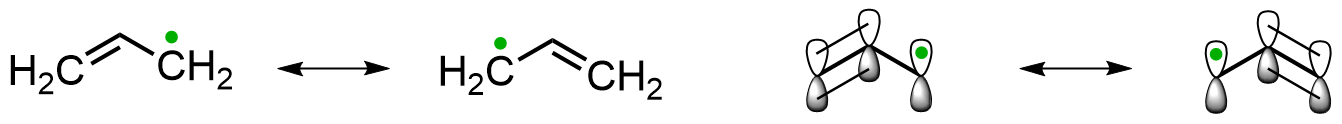

The allyl radical is a related species that features a half-filled p orbital on carbon such that C has 7 electrons. Having a neighboring pi bond will stabilize this species in a similar way to the allyl cation except only one electron is needed to help stabilize the radical; the second pi bond electron must therefore be accounted for in the second resonance structure by placing it on the third carbon of the allyl system. The typical allyl radical resonance structures are shown below (left) along with an orbital representation showing how the conjugated p orbitals interact.